I love my family. It’s currently the waning hours of a Thanksgiving weekend, and I’ve been watching NFL football while placing small wagers with my brother (capped at $20 per game), and enjoying some amazing food. It’s also, here in Chicago, the weekend of the first significant snow of the season. This view is from my flat’s second story window yesterday, with many inches falling since. But when I was growing up, my nuclear family, chockablock with accountants, made me doubt my own tenuous grasp on math and probabilities. They seemed to me to defy common sense.

To be fair, they were equally mystified by some of my decisions. Especially when I dropped ten bucks on a pair of deer whistles.

I guess I can thank my family for my iconoclastic streak. That, and back in the last century, school children were taught about Fulton’s Folly. From dinner table conversations of my youth I could relate to what Robert Fulton faced. He endured howling public ridicule when he built the first steam-powered riverboat. Critics called it a folly because they couldn’t imagine that something powered by steam alone could be viable in fast-flowing rivers. He proved them wrong, and I’m guessing educators of the day thought it was a good idea to talk about him to students, and, as Apple later told us, to Think Different.

Scratch that. I guess I should thank the Escanaba Public School system for my questioning of the status quo.

I fitted my car’s front-facing bumper with a pair of deer whistles, the size of squat hot dogs, to protect me from colliding with the prolific deer in our part of Upper Michigan. This was a time well before the internet. My evidence was scant — just word on the street. All I knew about deer whistles was that they were cheap, easily available at gas stations, and lore had it that Michigan State troopers tried them on their cruisers and reported a reduction in deer strikes. Today that story might be called too good to check.

Since then there has been considerable research into deer whistle effectiveness, and I find the research conclusive that they provide zero protection. But hindsight is twenty-twenty.

Here was my calculation: While the science to deer whistles was lacking, the costs were low. I had ten dollars to spare, and the cost of striking a deer could be in the thousands, and, on the ice and snow of Midwest winters, maybe also costing me my life. At best, they were harmless. But to my family? You would think I had decided to shop at my hometown’s meager mall, The Delta Plaza, wearing a red clown nose and giant floppy shoes.

When I reminded them of this cost / potential benefit analysis, they persisted in calling it a waste of money. We’re talking a family dispute, so of course I’d retaliate. I would remind them of the evidence that was already in about their weekly spending on lottery tickets, and the microscopic likelihood of a large payout and positive return-on-investment. That somehow didn’t score me any points with them.

Separating Dogma from Statistics

When the mRNA vaccine for Covid was released under Operation Warp Speed, and I read that there were vaccine skeptics, it reminded me of those family disputes. Because somehow having a whistle on my bumper was a signal to my family’s tribe that I was an idiot and a sucker.

Deer whistles, before social media — through pure word-of-mouth apparently — became a marker to the majority of Upper Michigan drivers of the breathtaking gullibility of their owners.

Are you surprised that community disapproval can be so strong without the aid of the tribal sorting hat called social media? Consider the hunting and killing of witches.

Actually, please don’t. It’s too bleak. Except I’m sure many witch hunters were convinced of their existance, and the righteous thing to do was quite obviously to put them to death. (Sadly, not all were sincere. There were incentives in othering small groups of vulnerable humans. Nothing has changed since then, alas.)

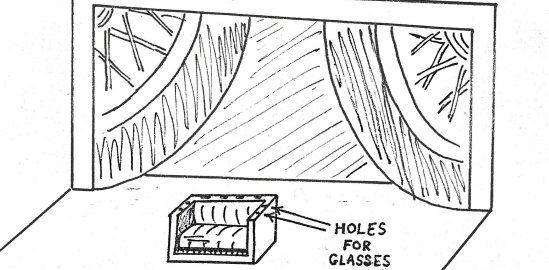

I thought of deer whistles when we were just coming out of the Covid lockdowns, and I was getting my first haircut by a professional, after months of doing it myself. Here was my Covid-era autohaircut:

Yeah, not pretty. The woman cutting my hair — a stranger to me I had chosen randomly to fix my terrible haircut — said she chose not to be vaccinated after doing her own research. She’d been watching YouTube videos that were supposedly from morticians, and they reported they would attempt to embalm people who had died after taking the vaccine and their blood had turned to powder.

I swear this is true.

She said, earnestly, “They interviewed, like, five morticians, and they all said they saw the same thing!” I was taken back to my youth. But she wasn’t my family, so I was less strident. I politely asked how many morticians she thinks there are in the U.S.

If a million people have died of Covid, maybe just those who have tended to those deceased are — conservatively — fifty thousand morticians. So assuming those videos weren’t staged, that’s one-ten-thousandth of all morticians who are reporting finding powdered blood. She didn’t take it well and I changed the subject.

Today, in spite of scoring a passable-but-not-extraordinary B+ on my university statistics classes, I know that Deer Whistle Tests are available to all of us. The only caution is to try to separate your thinking from the groupthink of the tribe you identify with.

The Doctor who Infected Himself to Solve a Medical Mystery

Tribes aren’t neccesarily anti-science. They can possess impressive levels of expertise. Here’s a famous and relatively recent example from medicine. It reminds me of the quote by German physicist Max Planck, who said, in frustration with his field’s groupthink, that “Science advances one funeral at a time,” as old ideas are only replaced once their defenders are deceased.

While I was disagreeing with my family about the utility of deer whistles, I was still trying to forget some of the meals I was compelled to eat at my childhood dinner table. My father had a stomach ulcer, and experts at the time said there was no cure, only a treatment. And that treatment was insanely bland food.

I still wince at the thought of eating one of my father’s favorite items out of the cookbook his physician had given him (actually, given to him to hand over to my mom). It was called Salmon Pie, and was a pie crust baked with a filling of mashed potatoes, dehydrated onion mix and canned salmon. Just the thought of its texture makes me wince, a half century later.

To quote the lede from this post, “Australian doctors Barry Marshall and Robin Warren discovered that H. pylori could lead to peptic (stomach and duodenal) ulcers. Having taken biopsies from patients with stomach ulcers and culturing the organisms in the lab, the doctors discovered the bacteria and its link to stomach ulcers following a clinical trial with 100 patients in 1982.”

This was a standard practice — culturing biopies — but physicians of the time called it folly, because they were convinced all the science that was needed was in: Ulcers were caused by stress and excessive stomach acid. These were communities of highly respected physicians.

Marshall and Warren were ridiculed when they presented their paper. The duo persisted for more than a decade. It’s possible ulcers might still be considered an incurable illness if Dr. Marshall hadn’t, exasperated, publicly dosed himself with the bacterium and induced a severe peptic ulcer within days. Then cured his ulcer just as quickly with the appropriate antibiotic.

Applying the Deer Whistle Test

Today I take multi-vitamins, in spite of my disdain for the unregulated supplement industry. I do it reluctantly, because of the Deer Whistle Test. Back then, the cost of trusting that deer whistles might be effective was $10. Today I spend that much monthly on the vitamins, knowing the worst that can happen is they do nothing.

Those are pro versus con calculations I can live with.